The Kallyope Yell

For SSAATTBB, reciter, and percussion (2 players) (2008), 8’30”

Text: Nicholas Vachel Lindsay

Premiered June 7, 2008, New York, NY; C4, the Choral Composer/Conductor Collective, with Daniel Neer, Reciter, Levy Lorenzo & Dennis Sullivan, Percussion, conducted by Benjamin Niemczyk.

Program Notes

Nicholas Vachel Lindsay (1879-1931) was renowned for his brash, dramatic, almost evangelical public readings of his poetry. Despite his rural Illinois origins, his work celebrated modern life and is frequently populist in nature. He was also highly original in his use of pure sound in his poems. It’s not surprising that he was not generally a favorite of the literary establishment of the early 20th century. A reporter once likened him to a circus calliope. Lindsay’s response was to “take ownership” of the word and the result is The Kallyope Yell. Significantly, in Lindsay’s identification with the inelegant instrument, he primarily uses its alternate spelling, namely the one that rhymes with ‘hope’.

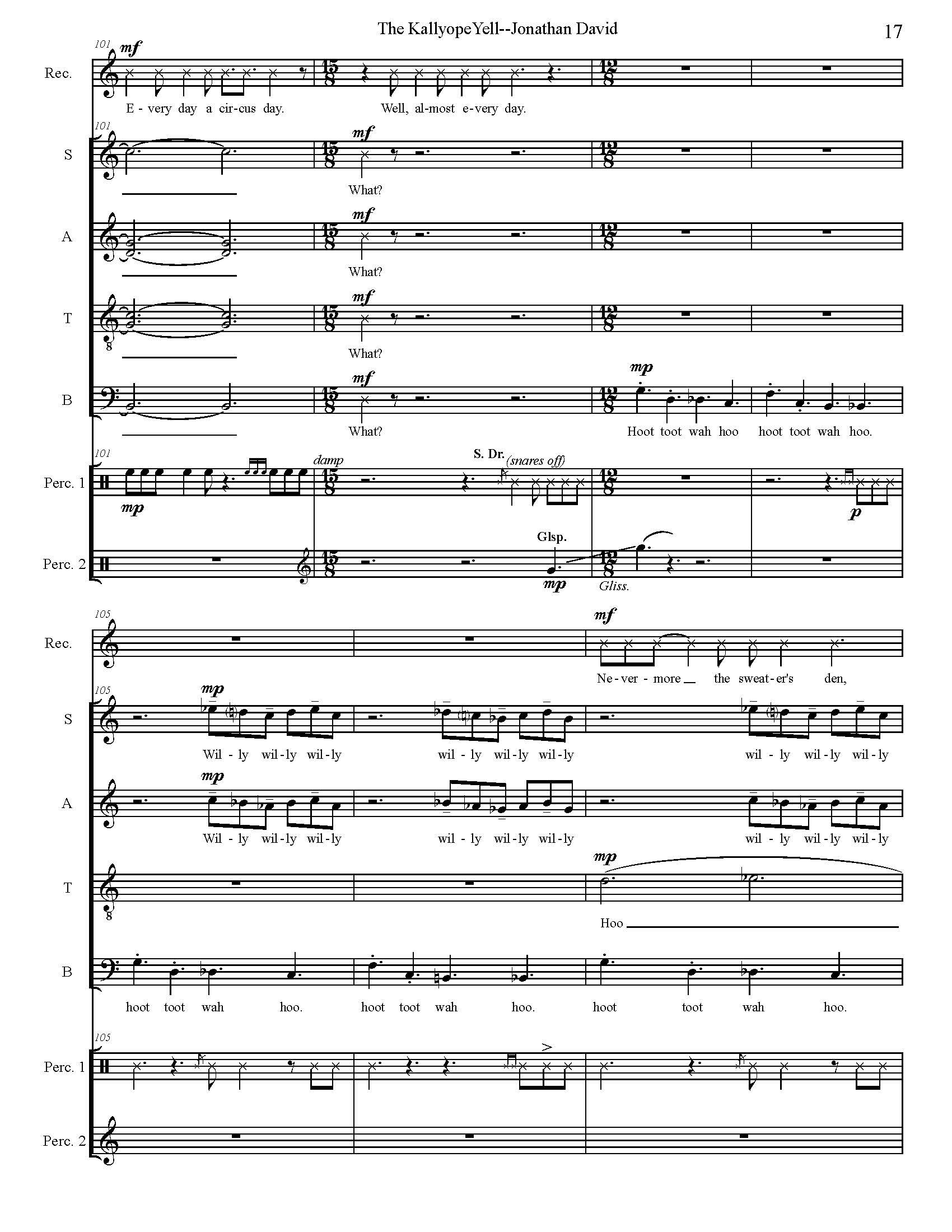

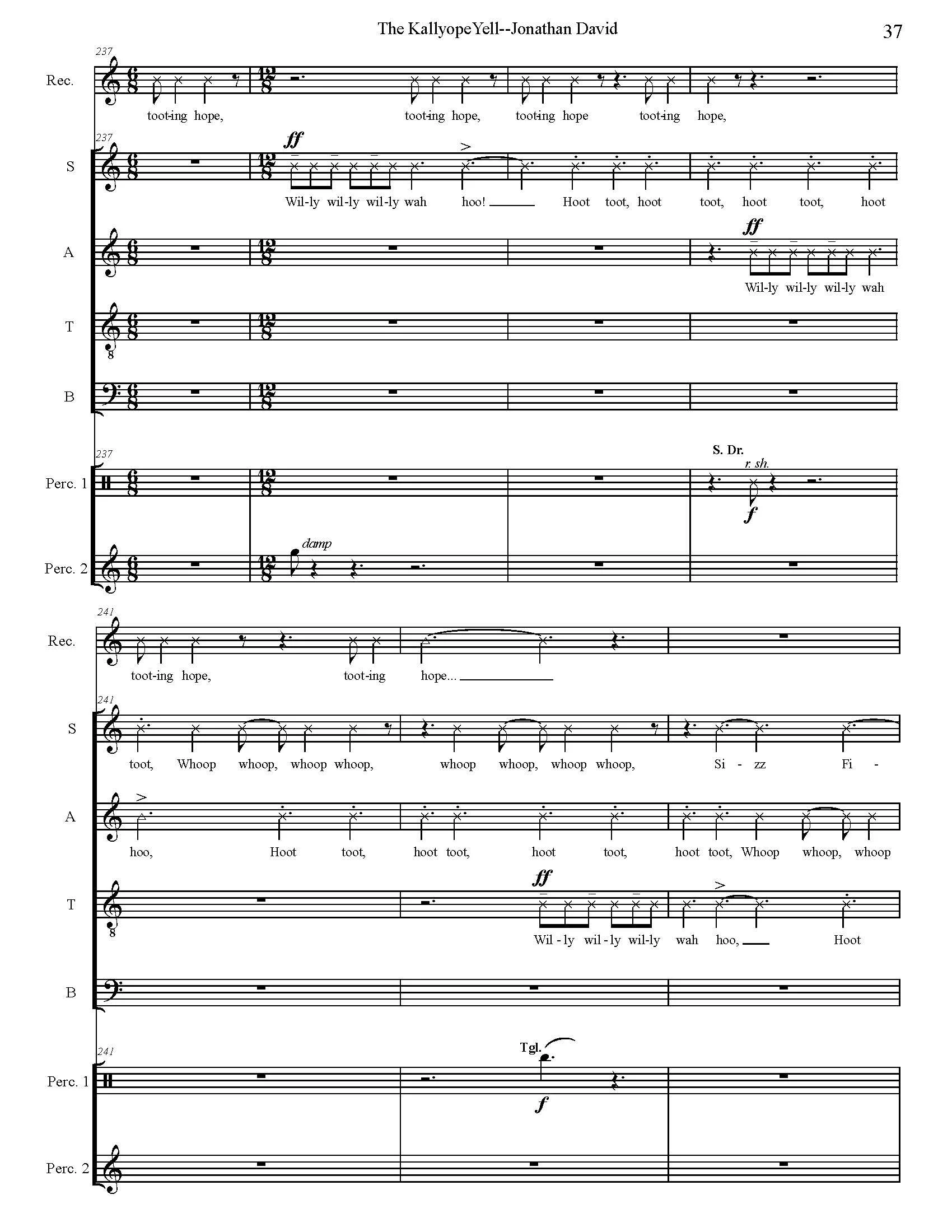

Lindsay uses the circus as an allegory for the modern world in all its raucous, democratic beauty. Significantly for him, though, the circus also has an orderly flow of events. Indeed, while the lion may roar, he is nonetheless tamed. In my setting, the percussion provides its characteristic clash and bang, but also a usually steady motoric pulse. The choral harmonies are advanced and often tonally ambiguous, yet they are “civilized” by their presentation in a theme and variations form known as a chaconne.

With Lindsay the reciter’s identification with the poet is even more pronounced. While the part is specifically rhythmicized, it leaves a high level of interpretation for the performer. For the most part, the chorus’ text is derived from the steam-powered sound world of the titular instrument: “Willy-willy-willy-wah-hoo, “sizz-fizz,” “ hoot-toot,” “whoop-whoop.” At a climax point in the work, however, half the chorus, won over by our preacher-ringmaster-poet, takes up the poem itself for the first part of the final stanza. The work soon closes with the orderly architecture of a rhythmic canon on Lindsay’s “noise” words.